Keenan Takahashi - Branching Out in Squamish

After many bouldering trips to the forest, Keenan Takahashi returns to Squamish with a new approach...

- - -

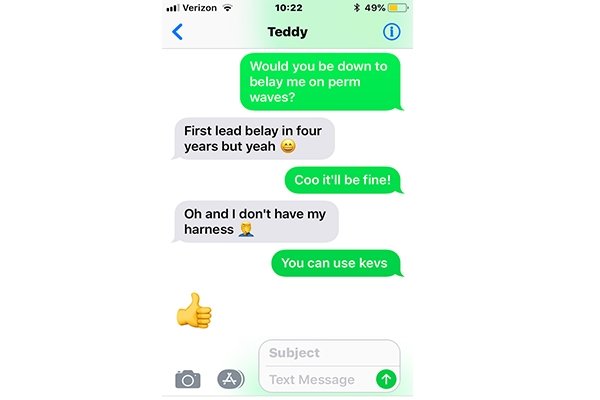

Seven years ago—my second trip to Squamish—I convinced my good friend Teddy to belay me on “Permanent Waves” (5.13d), a beautiful, obvious line on the back of the Cacodemon that follows a gently arcing rail all the way to the top of the massive boulder. The start is novel and fun—reaching the starting ledge of the route requires climbing a massive tree with huge spikes nailed into it. On that trip, I didn’t really know anything about the route other than the difficulty and that I wanted to climb it. My only other outdoor sport climbs had been two 5.10s at Mickey’s Beach in CA, so when I managed to flash to the second to last bolt, I was thrilled, thinking I was close to sending. When I fell, I tried to keep climbing to check out the rest of the route but got completely shut down. I couldn’t pull through, even with the bolts, and never made it any further.

Expectations

I’ve always tried things that were beyond my relative ability. I tried the “Mandala” on my first trip to Bishop, when I’d just climbed my first V5. Between bouldering trips last year, I went on my first dedicated sport climbing trip—three weeks in one of the most famous areas in the world, Céüse. The very first day, I tried “Biographie,” even though it was freezing and I hadn’t bothered to warm up. I love this: there’s no pressure, no stress, just psych and curiosity. Those early days teach me more than most; they’re humbling. I can see what others have been able to achieve, and understand how far I have to go if I want to reach even a remotely close level, let alone try to push beyond it. After a couple of weeks in Céüse, I experienced what it was like to be able to recover mid-route for the first time. It was then that I realized how long it would take to gain the necessary fitness to do a route at my limit.

“Dreamcatcher” (5.14d) is the most iconic hard sport route in Canada, but despite many efforts it has seen only six ascents. This year in Squamish, I met up with my friend Nick Milburn, who was also planning to try “Dreamcatcher.” Our first day on the route, he wanted to warm-up on “Permanent Waves.” He’s done it many times, and went first so that I could watch his beta for the section that I hadn’t gotten to try in 2011. Watching him float through the crux gave me confidence that it might not feel so hard now, so when I climbed up to the ledge for my first attempt, I told myself to really give a good effort.

Telling myself it wouldn’t be so hard now was probably where I went wrong. The whole route, until the last couple of bolts, is probably mid 5.12 climbing, but I persisted, over-gripping and working hard to get to where I had before. I managed to make it one bolt higher before pumping out, frustrated and wondering why it still felt so hard.

“It’s hard to be really bad at something… again.”

I rested on the rope for a few minutes and then started working out the final bolt, the real crux sequence: a few long reaches to get set up between two good (but sharp) crimps followed by the hardest move, a big right hand pounce to a good flake. From there, you can match and rest, and then it’s a fairly easy mantle.

While I was sussing it, the skin on my left index finger kept rolling and I was frustrated at how hot it was, which I also knew was just an excuse for not climbing as well as I’d like. I knew I couldn’t try much more or I wouldn’t be able to try “Dreamcatcher” after. My friend Paul Nadler and I talked about the proportionate effect that different factors have on a climb. We concluded that beta has the largest effect. Other factors—conditions, skin, crowds, etc.—aren’t make-or-break until the beta is perfected. I found a new method using a toehook; this made the move to the crimp static so I could save some skin. I finally linked the top section and asked Nick to lower me.

“It’s hard to be really bad at something… again,” I said when I got to the ground. It’s not uncommon for me to let expectations cloud my experience, and cause my focus to drift from the actual climbing to things that feel off. After bouldering for so many years, I’d gone into projecting the 'Catcher with an unrealistic expectation that I’d gotten better at sport climbing. I had, but the progress felt minute. Despite both being forms of climbing, bouldering competency doesn’t always translate to sport climbing (and vice versa) and you have to spend time adjusting to each discipline.

When you’re learning something for the first time, you don’t assume you’ll be good at it. When I first started skateboarding, I had so much fun, even though I was falling 99% of the time. When I took up climbing (bouldering), it was the same—falling all the time, but enjoying the learning process. I’d approached sport climbing as an offshoot of bouldering rather than something entirely new. I’d hoped to make the transition easily and be up there cruising, saving my energy and feeling strong at the crux section. Instead, I’d only made it a few feet further than my first attempt seven years prior. It was my first try of the trip, and I was more frustrated by this attempt than I almost ever am on any bouldering project. I was here to try to gain some insight on how to project sport routes, and now that it was time to start trying “Dreamcatcher,” I felt more hesitant than usual.

Projecting: Breaking it Down

Perhaps due to my background in bouldering, I like to split routes into different segments to not feel so overwhelmed. The ‘Catcher can be broken into four distinct sections, separated by rests—a nails-hard slab intro, a sloper section, the pinscars, and the final powerful boulder problem. This is followed by a vert face that, while sequence dependent, should be easily repeatable once you’ve unlocked the beta.

Keenan Takahashi battling heat to hang the sloping rail on "Dreamcatcher." Photo: © Kevin Takashi Smith

When it comes to projecting, a boulder problem or a sport route, the first step is to do all the moves, so that you know there is a possibility of linking them, then figure out how to optimize rests throughout the climb. On my first try, Nick ran me through move by move and I dogged my way up, stopping at any challenging section to figure out micro-sequences before allowing myself to go any further. Aside from the slab, I was psyched to do all the moves quickly and having done so, started focusing on linking the last boulder problem section. My two best attempts of that first session had me falling at the last move of this final boulder, an awesome dyno to a jug.

After my initial attempt, I started pulling through the slab section because the thin crimps wrecked my skin so quickly that it would compromise my ability to try the upper half. It was still 90 degrees every day and there was no reason to lose all my skin if it meant I couldn’t climb for the next three days! Starting a few bolts in also takes off any pressure as you are only trying to learn each section and improve your efficiency throughout the route. This is probably my favorite part of projecting—all you are thinking about is climbing; there’s no headspace for expectation or doubt.

I spent the second day on the route mostly working out the last boulder. This section is definitely the most powerful, and needs to be executed perfectly. Each move builds, and the holds are bad in a way that you can’t re-adjust on them. It’s tough to say which move is the hardest; there isn’t a single one that stands out as noticeably harder than—but every move is hard. The final dyno gave me a bit of trouble; maintaining the tension on the left foot is critical to be able to push far enough to reach the jug. Once I’d gotten all the micro-beta wired (mostly the foot positions where there are no feet; tension is created by optimizing body position on each hold), I managed to do this section twice in a row, and decided to try a few more links post-slab.

The first few times felt pretty rough; the sloper section is the easiest portion of the route, but also one of the most physical. I would arrive at the main rest sweating and breathing hard, unable to recover. The following pinscars involve very precise, static moves to take each slot perfectly, requiring a lot of body tension—if you’re pumped, it is hard to climb in such a controlled fashion. I was somewhat discouraged as making it to the first clip after this rest—using Nick’s beta—felt really exhausting. On my third day, I started to recover at the rest, and found a new way involving a longer lockoff to a slightly larger pinscar, cutting out two hand moves and making the clip easier. After that, you cross to the strangest and worst pinscar of the bunch, an upwards flared notch which you have to load almost completely on your ring and index finger. You roll off of this to a sloper crimp, and dyno to a slot jug, the final rest before the redpoint crux. In isolation, the jump wasn’t that hard, but coming from the first rest it gave me a lot of trouble. The now-standard beta involves using only a left foot and pixie-kicking to generate the distance. This felt quite extended though, so it was hard to swing my leg enough; I started to fall there a lot.

Inevitably, I spent a ton of time in the Room. A lot of it is just hanging out, staring up at the ‘Catcher’ and thinking about ways to improve. At the end of my third day, I’d just fallen on the jump again, and was starting to get frustrated. I realized I’d erred in not having looked for an alternate way to make the jump easier. From the ground I could see a general radius in which I’d want a right foot, and there was a small bump in the wall that stood out and looked promising.

An Old Nemesis

A couple of days after the first hiccup, I’d regained the psych to try “Permanent Waves” again and not force things.

Seven years after first trying the route, Keenan Takahashi recruits his original belayer for rope duty, again, on "Permanent Waves"

This go around everything went much smoother, and I found myself at the upper crux feeling a little bit pumped, but my time on the ‘Catcher’ had taught me I could still climb well even if I didn’t have 100% in the tank. Focused on execution of each move, and without expectation, I grabbed each hold as I’d rehearsed, stared down the final lunge, and snatched the final good hold. After mantling and clipping the chains, I lowered with a great sense of satisfaction, partly because I’d finished it, but mostly because I had put what I’d recently learned to use and that it had worked! To have Teddy belay me on both my first and final effort was special and brought everything full circle.

A Souvenir from Squamish

At this point, I’d put in three days on the ‘Catcher and time was running out; I only had two more climbing days. Earlier that week, I’d hiked up to Shannon Falls and was drawn to an amazing jet-black arête at the base of the falls. I’d put off trying it so I could focus on the ‘Catcher,’ but it remained lurking in my thoughts. On my last day, Kevin and I rallied with four pads and I immediately started going to work cleaning it and trying it, dropping off from higher and higher.

It’s quite committing, and I realized I’d have to do a high left heel hook from which there would be no return. Before the next try, I told Kev that I was going to go all in—when I got to the heel hook and locked off, I pulled up just short of a scooped angle change where I hoped a good wrap would be. I pinched the arête where I was, sucked my hips in more, and locked off as high as I could, barely reaching the scoop. Fortunately, the wrap was solid, and I delicately matched the arête, crossed up, built my feet, and reached to the top. Even though it wasn’t the hardest thing I’d climbed that trip, I was elated, and immediately exclaimed to Kevin that it was probably the highlight of my time in the forest! I later confirmed with the guidebook author that it was an FA, and I named it “Panta Rhei,” originally from the Greek philosopher Heraclitus and roughly translated as “everything flows."

Keenan Takahashi topping his first ascent, "Panta Rei." Photo: © Kevin Takashi Smith

It was already mid-afternoon when we got back to his car, but it was my last chance to climb so we headed over to “Dreamcatcher” anyways. I gave it a couple of goes, but again fell at the first dyno to the slot, this time my right hand dry-firing just before jumping. I was a bit disappointed to have not gotten to try linking past here, but my tendinitis was flaring badly and I was more exhausted than expected. I decided to call it and checked out a nice project for next time. A huge sushi dinner with a bunch of friends capped off a great last day and I felt the classic paradox of both satisfaction and already wondering when I’d be back.

If you are ever on the fence about taking a trip to Squamish, BC, take the leap and hop over the border. No matter what your favorite type of climbing is, it’s a safe bet you’ll find it on the bullet granite cliffs of the Chief, or amidst the boulders lurking in the lush forest below. My first trip to Squamish was in 2010, and I’ve been psyched to return every time; there’s always something new to try and seemingly infinite options to explore. Despite it being time to start focusing on fall projects, it’s proving difficult to get “Dreamcatcher” out of my head...

Preview Photo: © Kevin Takashi Smith